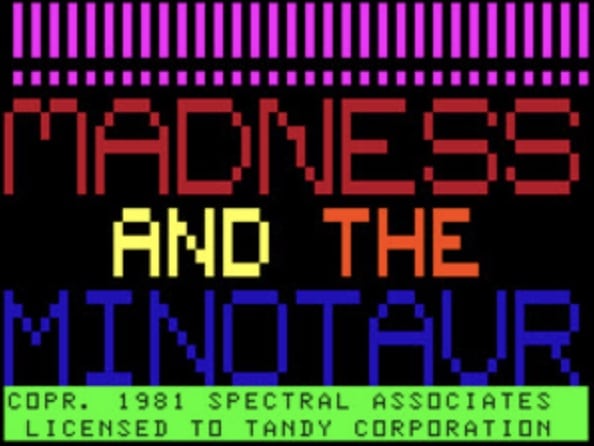

Madness and the Minotaur is a text adventure game for the TRS-80 in 1981 by Spectral Associates. It plays a minor role in the book Ready Player One.

Quote

I knew from my research that the cassette recorder functoned as the TRS-80’s “tape drive”. It stored data as analog sound on magneetic audiotapes. When Halliday had first started programming, the poor kid hadn’t even had access to a floppy disk drive. He’d had to store his code on cassette tapes. A shoebox sat beside the tape drive, filled with dozens of these cassettes. Most of them were text adventure games: Raaka-tu, Bedlam, Pyramid, and Madness and the Minotaur.

Game Play

As with Colossal Cave and other text-based adventure games (aka interactive fiction in the modern era, the player uses text commands (“North”, “West”, “Look”, “Open Door”) to navigate the game. It begins with a text prompt:

WELCOME TO THE LABYRINTH!! BEWARE OF THE MINOTAUR AND GOOD LUCK.

YOU ARE IN A NARROW HALL WAY WITH A TABLE AND A CHAIR. A GENTLY SLOPING TRAIL WINDS SOUTH. THERE IS A PASSAGE WAY TO THE WEST. THERE IS A NARROW PASSAGEWAY TO THE EAST. A GREAT HALL DISAPPEARS TO THE NORTH. THERE IS A LARGE OPENING IN THE CEILING.

Unlike Colossal Cave, it includes random elements that change the game with every replay. Specifically, the layout of the dungeon is always the same, but the location of key items changes with every game and there are random elements (magical gusts of wind, earthquakes) that can block your progress. And make the game extremely hard.

Impressions

I started off the game as I did the other text adventures in the replay, mapping them out in my gaming bullet journal and noting the various locations and their descriptions.

It quickly became obvious that this was going to be more challenging than the other games on the list. Magical forces pushed me out of rooms I tried to enter. Earthquakes cause interior collapses that block off room entrances.

I might actually need to read the manual.

Heck, I might need to find a walkthrough.

That’s what led me to Renga in Blue, an interactive fiction blog that did a series of posts about the game back in July 2021:

- Madness and the Minotaur (1981)

- Madness and the Minotaur: Mapmaking

- Madness and the Minotaur: The Two Manuals

- Madness and the Minotaur: The Third Dimension

- Madness and the Minotaur: Frustration

- Madness and the Minotaur: The End

My takeaway? Holy crap, is this a tough game. In author Jason Dyer‘s first game, he died in two moves.

Two. Moves.

Not only that, while playing the game, they realized that it happens in real-time. So how fast you move, how fast you make decisions, and how much time you spend mapping has real impacts on the game. For example, more time spent in the dungeon means more earthquakes. More earthquakes mean more closed-off passages. Ultimately, that means you can become trapped, and the game becomes unsolvable.

Whoa.

Jason goes to the extreme of creating a three-dimensional block map to try and understand the layout of the game’s four levels. which shows an impressive commitment to trying to solve a brutally difficult game.

But while the map is difficult, the randomness of the item placement – and exactly what items/spells are needed to slay monsters – makes figuring out what the hell is going on even more challenging. I have a ton of respect for Jason’s efforts here; he put in far more time and effort into this game than I ever would have.

Coming back to Ready Player One, this game points to one of the shortcomings of the book. As much as I enjoyed its endless pop culture references, too much of the book (and the movie) is based on grokking that pop culture. There are very few times when we see Wade Watts using skills he learned in games to find Halliday’s Easter Egg – for example, it would have been far more impressive if Wade had earned a key by solving cryptic logic puzzles and hell, reviewing (and maybe debugging) source code. Instead, he just needed to perfectly “play” the movie WarGames.

That may be challenging, but at the end of the day, that’s just memorization. Wade doesn’t learn a skill, and he doesn’t use that skill to improve his life (or solve the game). Looking back on all these games, that’s the actual lesson I learned. Breaking Monopoly on the Commodore 64 by mucking about with the source code taught me way more about programming than playing Pitfall ever did.

The Ready Player One Replay is an ongoing exploration of the games that inspired the novel Ready Player One by Ernest Cline. Love it or hate it, there’s value in revisiting our geeky roots.

High Scores

- My High Score: 0.

Madness and the Minotaur was indeed absolutely brutal.

I will be playing the sequel sometime later this year! Given I already have some of the schticks down I’m hoping it will go easier, but supposedly the monsters can pick up your scent and follow you so ???

Thanks so much for investing all that time in playing (and documenting) Madness and the Minotaur. It was a fascinating read, and it’s amazing how seemingly logical game design decisions can create such headaches for the players.

I’m definitely onboard for the rest of your text adventure journey. On my list, I still have Zork and Adventure in my future (your post about the myriad versions of Adventure / Colossal Cave is another great read; I had no idea how many iterations there were).